Damascus, Syria, Wednesday 11 November 2015

And, so, two months later, I accepted a controversial invitation to form a French delegation of politicians, intellectuals, businessmen and journalists, invited for an official visit to Syria.

Ironically, just three days after our arrival in Damascus, the Paris terrorist attacks at the Bataclan occurred.

Dama Rose Hotel, Damascus, Syria, Friday 13 November 2015

Our shell-shocked group, sitting in the marble-floored hotel lobby, began to joke: thankfully we hadn’t stayed at home, since obviously we were safer in Syria than in France! The event was tragic, but it somehow justified the audacity of this delegation coming here.

The next day we were granted an audience by the President of the Syrian Arab Republic, in his palace. Bachar al-Assad gave official condolences in a private audience, and then for the television crews waiting their turn. Publicly, Assad grieved for the French people, and he compared the hundreds of lives lost in this single event, with the daily losses to Syrian people through the war. His tone was bitter. There was a palpable “I told you so” in his words and manner, in his reproaching France of abandoning his country, of crushing his people with its embargo, of its support of the Americans and its blindness to Saudi Arabia’s double-dealing politics. He frowned too on Europe’s refugee-policy, saying that many so-called Syrians entering the continent were in fact terrorists sent by Daech using faked Syrian passports.

Damascus, Syria, Thursday 12 November 2015

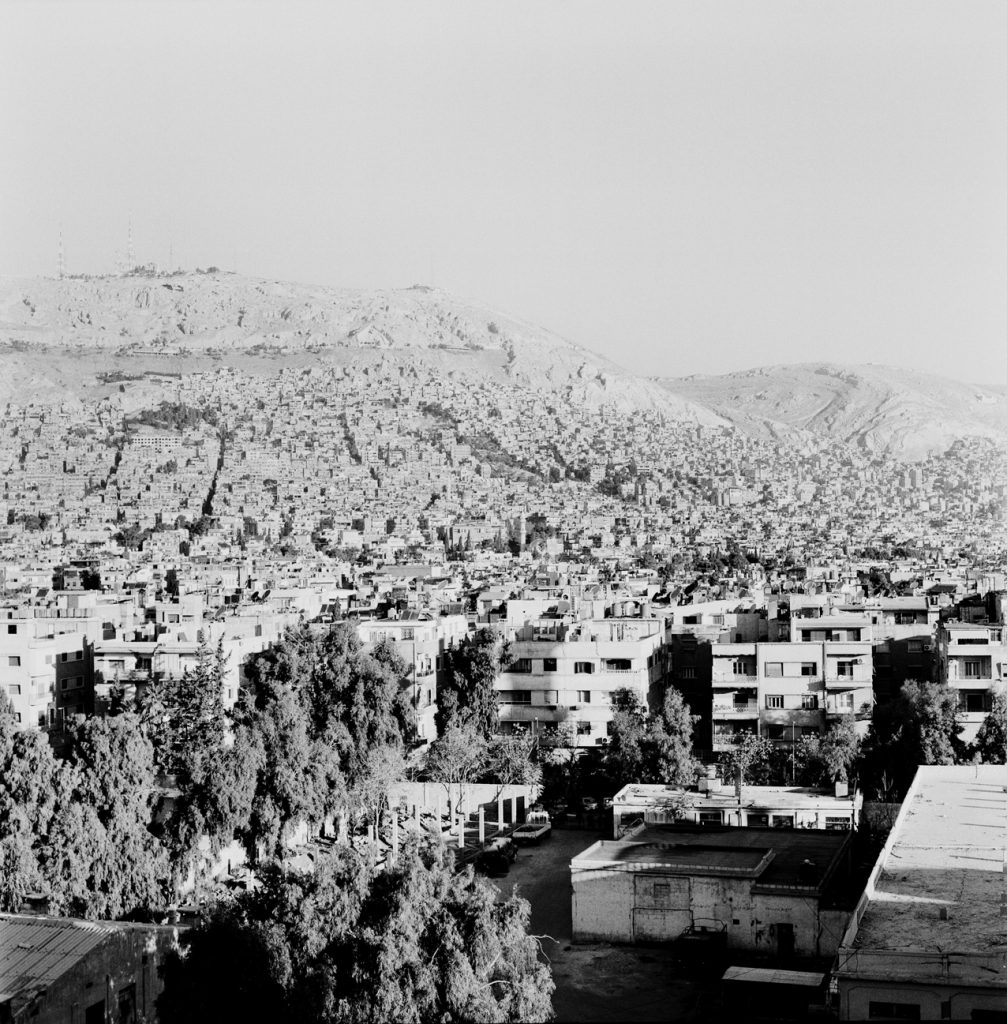

Damascus is a bustling, city which breathes history in every street. The streets were full of cars, the souk was crammed with people and little trucks making deliveries were constantly driving through the narrow aisles. The food was the traditional mezze — a colourful array of vegetables, salads, meats and spreads with bread. Wine was served at table, and aperitifs were either freshly-crushed pomegranate juice or chalk-white Arak, a liqueur made from aniseed. I felt distinctly unglamourous next to the Syrian women who wore lots of makeup, their hair styled in blow-waved curls. These birds of paradise ordered hookahs which were brought and lit for them at their table in the restaurant after their meal, filling the air with the smell of smoky apple… At our last dinner, I made the acquaintance of a young Syrian film director called Joud, who showed me rushes from his fiction film, The Rain of Homs, which he shot on location in the bombed-out city.

Earlier that evening as we wandered through the winding streets of the old centre, one inhabitant invited us in. The typical Damascene house is built in a rectangle overlooking a courtyard with a fountain in the middle. This courtyard was now communal as the house had been turned into smaller apartments. There were cobwebby lamps made from Damascus-blown glass hanging from the beams, and armchairs covered in worn striped silk.

This city is ancient, and is known as one of the few living mediaeval cities; as is Jerusalem. A few hundred metres and we were at Bab Shari— one of the city gates. It was distinctly dark by now and over the horizon was a reddish smoky haze and the sound of gunshots. That’s where the war was happening and we went no further.

From my hotel room I had a view of a minaret. I found the call to prayer very mysterious and soothing as it floated out on the evening breeze. The Grand Mosque of Damascus, or the Umayyad, was spectacular! I was handed a black robe with a gold brocade edging to wear over my clothing, and covered my hair with my dust-pink scarf, and removed my shoes. I was the only female inside the cordoned-off central area of the mosque, and was struck by the red Persian carpets covering the entire expanse of floorspace, allowing people to sit comfortably on the floor. In the middle of the mosque is Saint John’s Chapel, with green stained-glass windows lit from within, giving a garish glow.

The Grand Mufti of Syria, Ahmad Badreddin Hassoun, received the delegation on the first evening. Persona non grata in Europe, he had just been to Russia where he had been received with honours. His discourse was eloquent and convincing. In France, we were nursing vipers in our midst by permitting the construction of Saudi-funded mosques. Were we bent on our own destruction? He told us about how he had visited the prison to meet the men who had assassinated his youngest son, Saria, a student at Aleppo university, in 2012. “I said to them : ‘I forgive you’ and I asked the judge to forgive them…” His message of reconciliation and tolerance was moving, his notion of a secular government being the only way forward, was stated clearly. He remarked that Germany’s Christian Democratic Union would do well to rethink its name, and that countries like Turkey and Syria strongly need secularism to survive.

Ma’aloula, Syria, Friday 13 November 2015

On a hilltop is the ruin of the Al-Saphir four-star Hotel. The building is gutted, and twisted remains of a playground nestle between two pine-trees, miraculously left standing. Unable to resist, I climb into the metal swing and am soon flying back and forth on the end of the solid chain.

Ma’aloula, northeast of Damascus, is an ancient town recently taken over by Assad’s loyalist army from Daech. A long detour avoided the direct road, unpracticable because of snipers. Ma’aloula apparently had over twenty churches, some of which had been razed, others which had suffered mild damage, but were ravaged on the inside, icons defaced and walls burned. They were reconstructing as we made our visit.

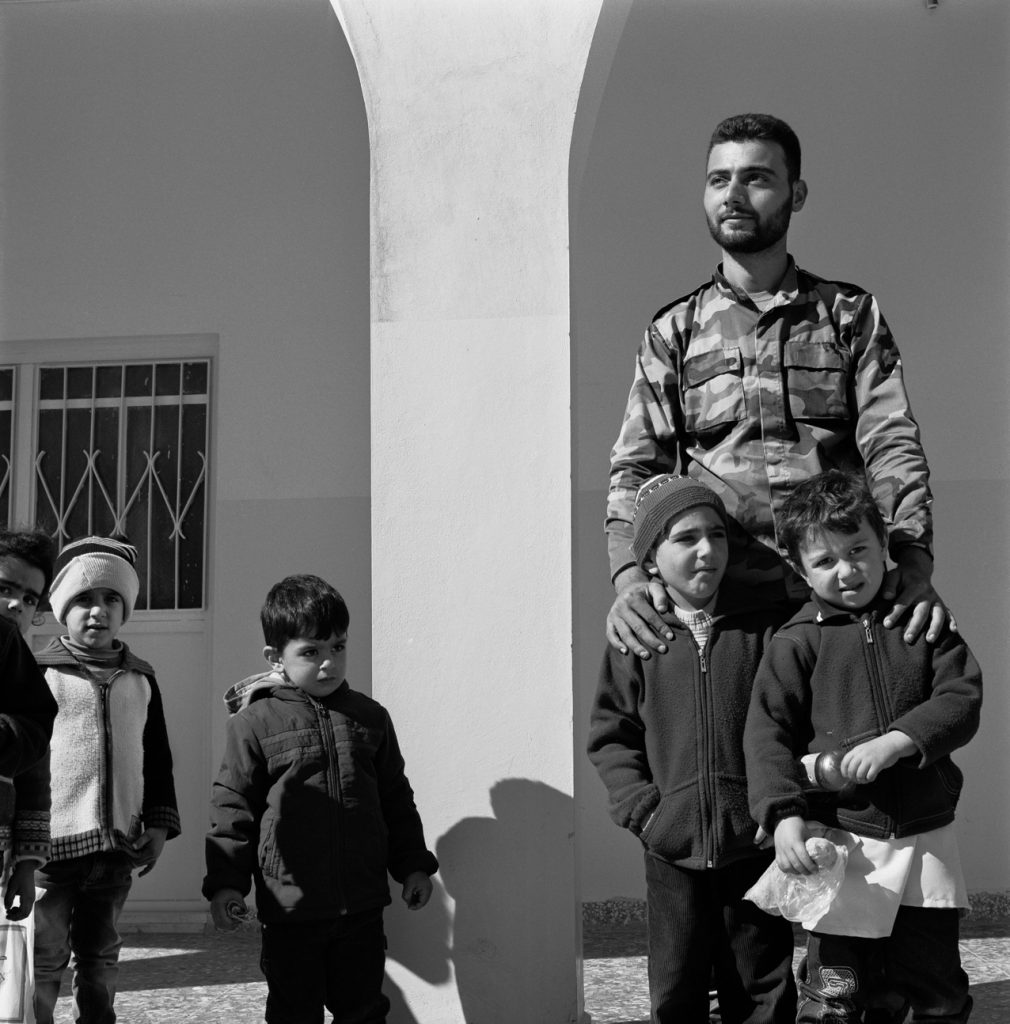

Stepping out onto a sun-drenched terrace of the devastated St Sergius Monastery, overlooking the town, we found a blind man sitting at a small table with a pot of tea. He offered us a glass and one of the French deputies accepted with pleasure, sitting down in the empty chair beside him. Ma’aloula is built into the rocks. Its churches with their oriental domes gleamed in the wintry sunshine, shadows of crosses deformed on their metal surface. It was almost deserted however, and the school that we saw was guarded by militia.

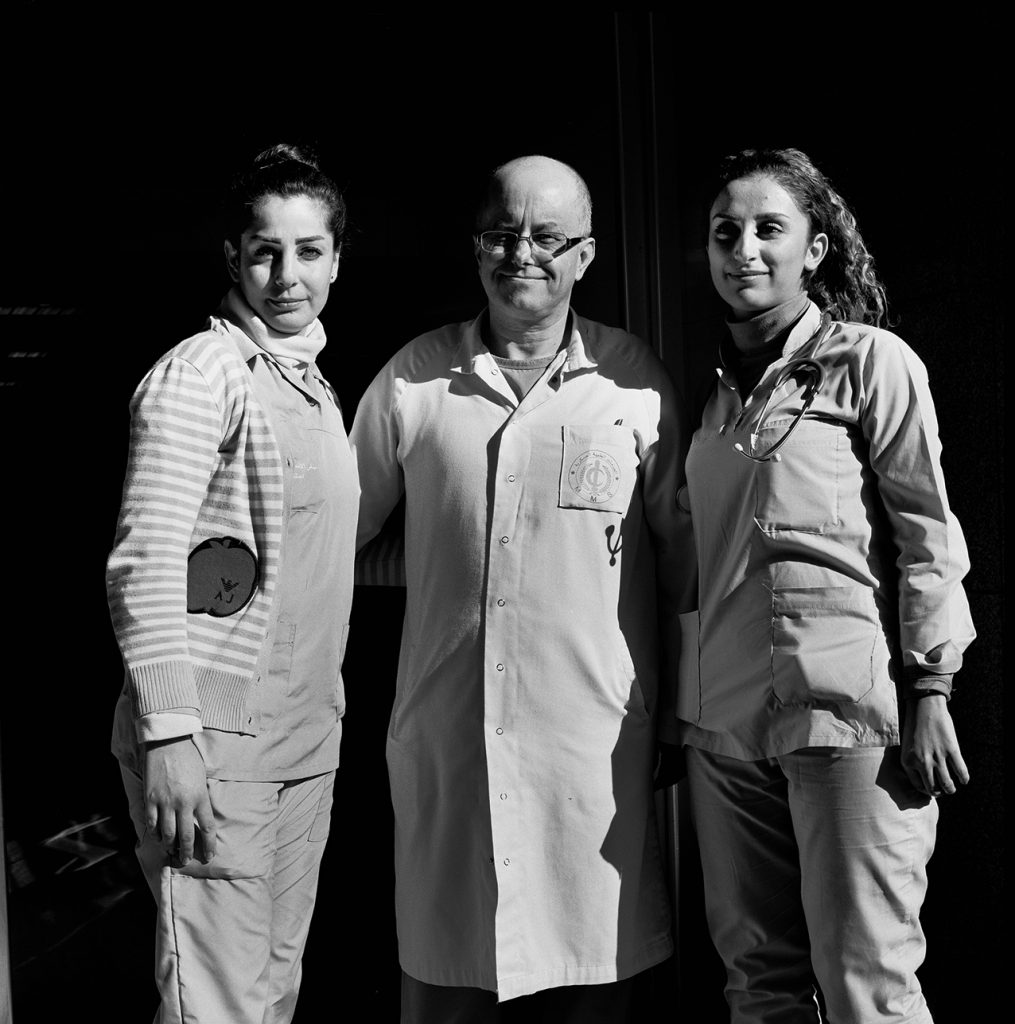

Heading back to Damascus, we stopped at the Tichrine Military Hospital on the outskirts of the capital. Whilst we were there, a stretcher was brought in with a wounded (Russian?) soldier covered by a sheet. The war was most certainly happening somewhere out there… Hospitals are hampered by the sanctions on Syria. Basic medicinal supplies running low and hard to obtain. Before we left, I took a picture of Dr Darmish and two of his nurses — strikingly beautiful women with green eyes… We left, our pockets full of little cakes which the doctor gave us.

Our visit over, our audience with the dictator fresh in our minds, we returned by road to Beirut, no direct flights being possible from Syria.